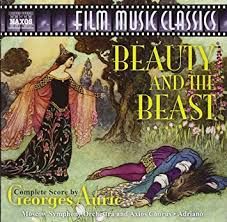

Music Composed by: Georges Auric

Music Conducted by: Adriano

Music Performed by: Moscow Symphony Orchestra & Chorus

Movie Genre: Fantasy

Movie Release: 1946

Soundtrack Release: 2005

Label: Naxos

“If you are looking for fantasy soundtracks

from an era when composers wrote music as valuable as gold

and as timeless as love, then the score of “Beauty and the Beast/

La Belle et la Bete” (1946) is not to be missed!“

The most famous story of Jeanne-Marie Le Prince de Beaumont, although it was published for the first time in 1757 as part of a fairy tales anthology, it remains charming and popular up to this day. The Beauty and the Beast story counts many film and TV adaptations that made history and were loved by the followers of both mediums. The era, settings and some individual aspects of the story may change, but the beauty’s love for the beast remains the same, offering one of the best romantic stories ever. A love story, in fact, that emotionally affects deeply the viewers. To all the story’s adaptations for TV or cinema, music has been the most important component and valuable asset for setting the atmosphere. It is the atmosphere that makes the fairytale believable, the beauty’s love real and transfers us to a world where anything is possible. If there is love, even a beast can be transformed into a prince.

The first appearance of beauty and the beast’s story on the big screen was on a black and white French film in 1946, directed by Jean Cocteau. Needless to say, it caused a sensation. The director calls on viewer’s childlike innocence by mentioning immediately after the movie’s opening credits the following line: “Children believe what we tell them. They have complete faith in us. I ask of you a little of this childlike sympathy”. Why to use such a prologue for? Well, in 1946 movie goers were accustomed to watch conventional stories in cinemas, rather than fairytales with strong imaginary elements. However, luckily for the director, the prologue was not the only thing that helped the viewer adjust to a considerably different movie with an imaginative story. What sets the mood so that the viewer would feel comfortable as he enters the movie’s world is the music composed by Georges Auric, who has previously worked again with Jean Cocteau. However, this score is assumed to be their most significant one.

Georges Auric (1899-1983) begun composing movie scores in 1930, after having excelled at ballet music composition. Being one of the most significant musical figures in France, he will be charmed by cinema’s musical potential and will compose scores for domestic productions, including eleven movies of Jean Cocteau, along with others in the United Kingdom and the USA. Some of his most famous scores were those composed for the movies “Moulin Rouge” (1952), “Roman Holiday” (1953) & “Bonjour Tristesse” (1958), for which he collaborated with three leading Hollywood directors, John Ηuston, William Wyler & Otto Preminger respectively. In 1962, he abandoned film scoring, since he began working as a conductor for the Paris Opera. There is a specific reason why his music for “La Belle et la Bete” (1946) stands out through his collaboration with Jean Cocteau. It is the same reason why this score is now considered as a milestone in his career, a milestone for French movie making and a milestone for combining images and music in the big screen in general. It’s because the music doesn’t follow the moving images! It sounds strange but still, a substantial part of the score was not synchronized with the movie, a most crucial procedure in movie scores. Music is supposed to follow the scenes and serve their needs. This is not the case for “La Belle et la Bete” (1946) and, in fact, there are scenes where the music moves to a completely different direction compared to the images. A deliberate intention or just an accident?

The disobedient, so to speak, score compared to the frames was a forced accident. The reason was that while Auric was composing the score, editing had not yet finished. The final copy of the movie was different than the one the composer had in mind while writing the music. As a result, the final visual product wasn’t in total accordance with the final musical product. Logic says that this king of a situation can be characterized only as utter disaster: instead of helping the story the movie narrates, music undermines it. Or so it seems. It may seem impossible, but this mismatch of music and images, miraculously, boosts the cinematic outcome and captures the viewer in a unique experience. This spontaneously at times progression of the music neither harmed the movie, nor led it to disaster, but instead revealed new potentials for its usage and significantly helped a movie that narrates a fairytale. The fact that we are dealing with a fairytale certainly helps this situation and allows for another, alternative interpretation of the movie’s musical score. If the story was not about a fairytale but a today’s conventional story, then there would be a problem and the music would indeed lead the production to complete failure. Along with the fictitious element and the bold story, the frames move in their own way, where the music many times clashes with, by either overly highlighting everything that is happening or reaching the point where it stops abruptly. And then? Just silence. This way, silence is emphasized as a musical tool and speaks in her own special way. The director attributed the successful outcome of the coexistence of images and music to the fact that his visual narration neutralized the musical narration of Georges Auric and vice versa.

Silence in musical terms not only helps the scenes where music is non-existent, but also the following ones that are escorted by the music. This musical absence makes the presence of the music more significant and amplifies the way the music affects the viewer when it returns. At this point, it is the ideal moment to bring ourselves to the position of a movie goer in a dark theater of 1946, where without a doubt he was thrilled to watch “La Belle et la Bete”. Besides the countless differences with today, there is one crucial difference that vastly affects the music’s role in the movie and its influence on the viewer: the complete lack of sound effects. Nowadays, we are used to movies awash with sounds and any kind of sound effects that cover the music, but it is difficult to understand how important their lack is; it gives the music the chance to work its own magic and holds the attention of the viewer. Only then music is able to give the 100% of its power and this is exactly the case at “La Belle et la Bete”. When the movie was released at the cinemas, it might not had been in color, but this was attributed through the music. One could describe this cinematic experience as magical, with Georges Auric’s compositions seducing the viewer by either being enforced or shining through their absence.

Once upon a time, an elderly father of three adult daughters crosses the woods when a storm changes his direction and leads him to an abandoned castle, or so it seems to be. As a souvenir from his short stay, he cuts a rose from the garden and then a beast appears in front of him. As an exchange for his blasphemous action, the beast forces him to choose between his own death and the death of his daughter, Belle. When the father returns to his house and describes everything that happened, his daughter Belle is willing to sacrifice herself in order to save her father and leaves to find the beast at its castle. An unusual cohabitation begins and gradually Belle falls in love with the beast. When the beast succeeds in bending Belle’s resistance and makes her not only get used to his nightmarish looks but also love him, Georges Auric will make you believe that everything you see is part of a living dream. Soon enough you will fall in love with his music. The score brings a dreamy atmosphere to the movie, making the viewer believe that the frames in front of him come straight from some dream. The director focuses in the creation of the atmosphere and uses the music in the best possible way for serving the picture. In other words, he does not follow the usual tactic of composing musical themes for the movie’s characters that would be repeated or adjusted depending on their emotional transitions. In the case of “La Belle et la Bete”, George Auric is not embracing the motif and its technique.

The first noticeable absence regarding the score of “La Belle et la Bete” is a love theme for Belle (beauty) and the beast. The most common thing in cinematic love stories is a musical theme representing the feelings of love and devotion between the couple. Auric’s music presents an alternative idea that escapes from the usual frameworks and is proved quite right. This particular love story does not require a love theme because it does not need one. Besides, the lack of a love theme is a unique message for the score listener and movie viewer; in that way the couple is idealized as special to all others. This differentiation is outlined through the absence of a love theme. If you want to idealize something you need to distinguish it from what is widely or commonly used. In order to mesmerize the viewer from the very beginning and catch his attention, music starts dynamically with the orchestra’s brass section during the opening titles in “Générique/Main Title” (#1). It is an era when it was impossible for movies not to have opening credits, contrary to nowadays that it is a common practice that deprives the composers of the chance to affect in many ways the viewer’s psychology during the beginning of a movie. Following the brass section of the orchestra, the violins are changing the mood and preparing the viewers for Belle’s appearance. Right before passing the torch to the next piece of music, the track returns to its loud self with a crescendo. Soon, music of equal emotions is to be expected.

When the father is lost in the woods during a storm, the music in “Dans la Forêt/In the Forest” (#3) utilizes the intense sounds of the brass and percussion sections of the orchestra in order to be in harmony with the fierce moods of the weather. When Belle’s father arrives at the abandoned castle, the choir is heard for the first time in “La Salle des Festins/The Banquet Hall” (#4). This musical effect, enchanting and threatening at the same time, is not used by accident. Competent and serious film music is never placed by accident. The usage of the choir from this point of the movie to its end suggests the presence of the beast living in the castle. However, it refers to its spiritual presence, not its physical. The later is reflected by the orchestra with turbulent music when, for example, the beast appears for the first time and threatens Belle’s father for the rose he cut from the garden in “Le Vol d’une Rose/The Theft of a Rose” (#5). Moreover, the ethereal choir is called in order to express the beast’s feelings when he shares the castle’s rooms or its garden with Belle, chatting with her. When we hear it in “La Salle des Festins/The Banquet Hall” (#4), while Belle’s father is entering the castle without seeing the beast, it suggests the owner’s eternal presence everywhere; he is present even though he is not seen. He watches everything, although he is absent from the screen. The choir glorifies his presence via his physical absence.

Belle decides to offer herself to the beast in order to save her father from death and gallops to the castle, as is so characteristically described by music’s adventurous mood in “Départ de Belle/Beauty’s Departure” (#7). In order to enter the castle’s main hall, Belle will need to cross a dark hallway lightened only by candlesticks held by human hands on the walls that are moving forward in order to lighten her path as she is passing by. This is the most distinctive scene of the whole movie, in which images are marked on the viewer’s memory, who notices that music offers Belle a gentle touch in “Les Coulouirs Mystérieux/Mysterious Corridors” (#8) and surrounds her with affection and love, just like beast’s emotions for her. Choir’s appearance, whose vocals are performed with a closed mouth this time, attempts to hypnotize Belle and when the vocals return to their normal form with a slightly mysterious tone, it is like a twisted force is trying to seduce her. Beast’s force wanders everywhere and has already begun to subconsciously affect Belle. As the time she will meet the beast’s physical form approaches, music changes and at the end of the track it becomes more agonized and restless. “Apparition de la Bête/Appearance of the Beast” (#9) certifies the beast’s appearance in front of Belle and the orchestra bursts into a music sequence of repulsion followed by a steady mysterious atmosphere.

The choir returns to the music when Belle and the beast meet in the dining room. In “Le Souper/The Dinner” (#11), vocals are no longer as angelic as before but they reveal menace. They reveal beast’s despair for Belle’s negative answer in marrying him. Her negative answer infuriates the beast and the choir’s change into a more nightmarish tone becomes more evident in this track and continues without notable change in the following one, “Moments d’effroi/Frightful Moments” (#12). In “La Farce du Drapier/The Durlesque of the Draper” (#13) there is a change of the atmosphere with a very likeable and gentle scherzo that did not found its place in the movie. The dialogue between Belle and the beast when they are strolling at the castle’s garden is accompanied by “Les Entretiens au Parc/Conversations in the Park” (#14) and the music finally has a romantic mood, just before Belle manages to persuade the beast for something she desires much; allowing her to go back to her house and see her family with the promise of returning soon. In “La Promesse/The Promise” (#15), the choir emphasizes on the beast’s troubled and sad feelings. Belle wants to leave him and violins become more sorrowful than ever. Just before the movie’s end, the orchestra is called to honor the story’s ending with a pompous manner and utilizes all of its musical instruments by offering a special epilogue that is proper for an engaging love story that is like no other!

The release of Naxos (2005) is the second in row of the same recording made in 1994 by maestro Adriano conducting the Moscow Symphony Orchestra. If the original recording was released, it would be in any case problematic due to its old age; it’s something that has not happened until today as it is considered to be lost. In 1992, the maestro found George Auric’s orchestral score in a pile among other of his compositions, stored in boxes. After a very tiring procedure of identifying and collecting every sheet of music from the soundtrack of “La Belle et la Bete”, he carefully studied them and recorded the whole score from the beginning for the first time after 48 years! Many of the tracks were used fragmentary, while others were not heard at all, such as “La Farce du Drapier/The Durlesque of the Draper” (#13) & “Proposition d’Avenant/Avenant’s Proposal” (#20). As a result, the modern recording of the music gives us the option to study the score in a more complete manner, which the composer wrote as a symphonic poem.

Thanks to Adriano’s exceptional recording, we can all enjoy and admire this particular musical masterpiece of the big screen that would otherwise remain forgotten. If you are looking for fantasy soundtracks from an era when composers wrote music as valuable as gold and as timeless as love, then the score of “La Belle et la Bete” (1946) is not to be missed!

Track List:

01. Générique/Main Title (2:04)

02. La Belle et Avenant/Beauty and Avenant (1:26)

03. Dans la Forêt/In the Forest (3:16)

04. La Salle des Festins/The Banquet Hall (3:36)

05. Le Vol d’une Rose/The Theft of a Rose (1:49)

06. Retour du Marchand/The Merchant’s Return (1:00)

07. Départ de Belle/Beauty’s Departure (1:38)

08. Les Coulouirs Mystérieux/Mysterious Corridors (3:38)

09. Apparition de la Bête/Appearance of the Beast (1:39)

10. Dans la Chambre à Coucher/In the Bedroom (1:19)

11. Le Souper/The Dinner (3:40)

12. Moments d’effroi/Frightful Moments (4:14)

13. La Farce du Drapier/The Durlesque of the Draper (2:52)

14. Les Entretiens au Parc/Conversations in the Park (4:01)

15. La Promesse/The Promise (2:07)

16. La Bête Jalouse/The Beast’s Jealousy (1:30)

17. Désespoir d’amour/Love’s Despair (1:39)

18. Les Cinq Secrets/The Five Secrets (4:04)

19. L’attente/The Waiting (2:08)

20. Proposition d’Avenant/Avenant’s Proposal (1:26)

21. Le Miroir et le Gant/The Mirror and the Glove (3:30)

22. Le Pavillion de Diane/Diana’s Pavillion (4:17)

23. Prince Charmant/Prince Charming (2:51)

24. L’envolée/Flying Upwards (2:23)

Total Time: 62:08

The tracks that stand out are noted with bold letters